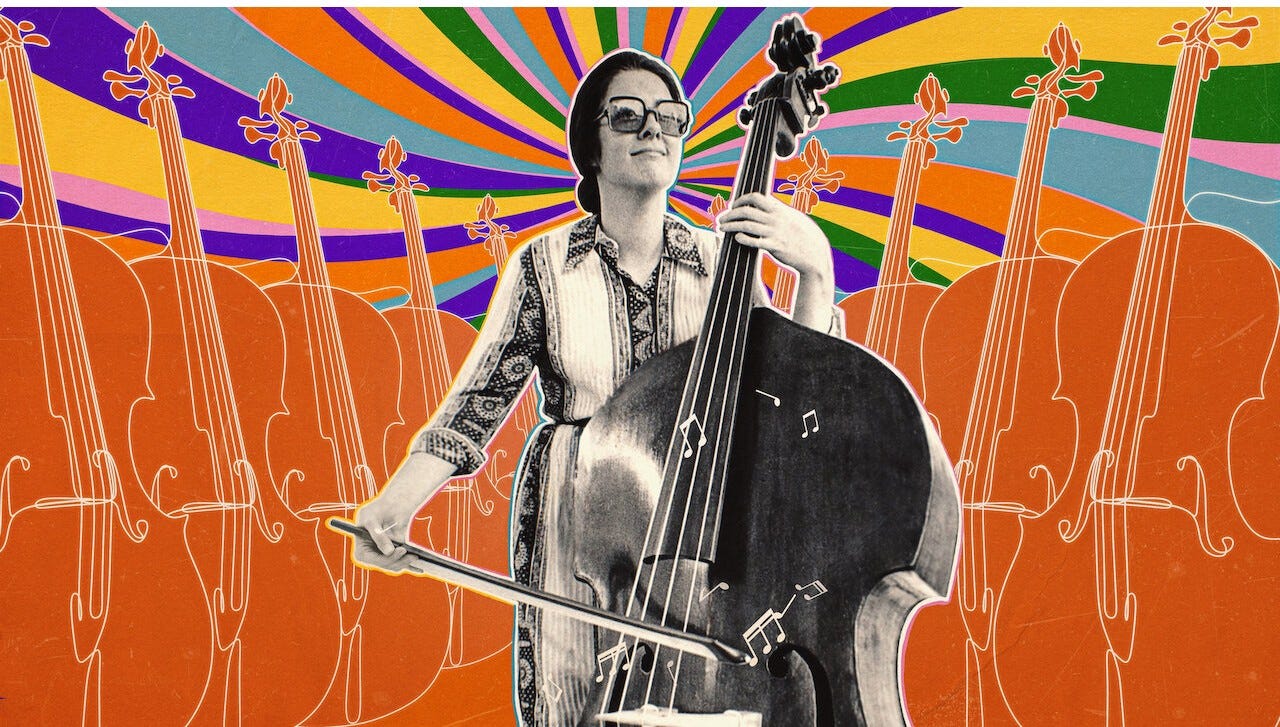

In 1966, Orin O’Brien was hired to play doublebass in the New York Philharmonic. Her conductor was Leonard Bernstein, who called her “a miracle.” She was the first woman to ever earn a seat in that orchestra.

Further, as The Only Girl in the Orchestra—the Academy Award-winning, very short documentary on Netflix—depicts, no part of the implications of that last sentence was lost on Ms. O’Brien. The film was directed by O’Brien’s niece, Molly (not Tim O’Brien’s wife Mollie).

I won’t spoil any of the film’s too-quick thirty-five minutes by sharing O’Brien’s backstory, but I will urge you to watch it if you’re at all interested in music and history and humans … and, well, ideas in general.

There is something O’Brien says in the film, however, that I will quote here, because it matches advice I was given back when I was trying to make my way through the New York City singer-songwriter scene. It is, perhaps, one of the things that inspired me to walk away from something into which I had sunk so many years years and every physical and emotional bit of energy I possessed to that point.

“You start with a passion for the sound of your instrument,” she says. “Loving to play, loving to play with other people, loving certain kinds of repertoire. But if there’s anything else you enjoy doing as much as playing the bass, by all means do it.”

Of course, I was playing guitar and I was doing it in very different quarters than Ms. O’Brien—whom, it occurs to me, was in the Philharmonic while I was in Manhattan singing into beer-stank microphones downtown. What a missed opportunity. I could have seen her play.

Anyway, this is advice that exists among musicians. It’s out there floating in the zeitgeist, getting passed around like one of those Dunlop guitar pics I continue to find in the randomest moments and places.

As it turned out, the only thing I could see myself doing other than writing and singing melodies was writing sentences. It was more of a lateral move than anything, and I’ve wound up making a career of writing sentences about other people who make music. (There are many other kinds of sentences I write.) But I’ve also spent a lot of time thinking about this idea that we should put away our art if there is anything else we’d like to do.

A month or so ago, I wrote in this space about imposter syndrome and how many artists I know struggle with it, and how I believe this is because we’re told from a young age that there’s no future in the arts. I don’t think that’s what Ms. O’Brien meant, though, and I don’t think that’s what the guy meant who once told me basically the same advice (no recollection of his name, but he was an incredible guitarist). Indeed, I have never stopped making music, nor writing it, though these days my “songwriting” consists mostly of making up songs on the spot that will make my children laugh.

For Ms. O’Brien, you can see in her face, as she rehearses the Prokofiev with a colleague in a teensy practice room, that the extraordinary potential inherent in two or more people playing music together truly moves her. That facial expression is equal parts wonder and grief that this moment should ever have to pass.

It is the face of a person responding to the vibration she feels in her shoulder and her fingertips and the wrist of her right hand, as it bows across these very thick, very taut metal strings. Indeed, just as there are monitors on the stage at a rock show to make sure everyone onstage can hear one another above the noise of the room—a mix of music specific to the band, separate from what the audience is being fed—so too is there a singular experience of music experienced only by the musician.

Watching this documentary made me want to give that some words on a screen.

I have felt this vibration from the body of my guitar. I have felt it from piano keys and from the long metal tube of a flute or somewhere behind the flare of the trumpet. It is a part of music making that we don’t really talk about much, because often the part of music people want to ask about is their experience of the music. That is the thing we have so many words for. That is the experience of the person or people on the receiving end. But there is music that only the musician knows.

There is the vibration of the wood and what happens to your nervous system when you’re holding the thing in the proper way, playing it with intention. The buzz of your emboucher against the trumpet mouthpiece. The split-second buzz against your fingertip when you pluck the next note, when you bend a string against the fretboard.

Music, after all, is nothing more than manipulated vibration. It is air and sound pressed from one person to another, or to many at once. That same spurt of air and sound can literally move water. If you place a speaker in a tank and turn on music, the vibration will make waves. Our bodies are 60-70 percent water, so you do the math.

There is a service the music provides to the player in that moment, and no musician—O’Brien and my old friend whose name I’ve forgotten, included—would recommend anyone stray from that side of the music.

After all, O’Brien spends much of the film trying to make abundantly clear that she believes there is great value in musicians supporting musicians. In the power of collaboration.

At one point, she tells her students to stop trying to shine. “You’re the floor under everyone else that would collapse if it wasn’t secure,” she tells them.

Honestly, I don’t know how to end this piece other than to say: Watch The Only Girl in the Orchestra then come back and tell me what it made you think about.